1960s New York: A Lasting Source of Inspiration

Photo Essay ★ Jenna Kaufman ★ @jennakaufmanphoto ★ 11 Minutes

In the early 20th century, the "American Dream" took hold as an idealized vision of prosperity, family life, and upward mobility. Traditional gender roles were firmly in place: men were expected to be breadwinners, while women were largely confined to the domestic sphere. However, by the 1960s, this vision began to fracture with the rise of countercultural movements that challenged mainstream values.

These movements were rooted in anti-establishment, anti-materialist, anti-war, and civil rights ideals. Writers, poets, and musicians became key voices of dissent. The music of the era reflected these radical shifts, as artists pushed the boundaries of sound and lyricism in defiance of conventional norms. New York City, a cultural crossroads rich in diversity and artistic energy, became a vibrant center for this counterculture. It was a place where creativity flourished through protest literature, experimental music, and communal spaces that fostered a shared vision of social change. This summer, I took it upon myself to research and photograph key locations from the history of music and counterculture in New York, in an attempt to connect how music impacted and still impacts communities and society as a whole.

Expression and the rejection of societal norms were a large aspect of the counterculture movement. The evolution of pop music in the 1960s is one of the most poignant changes that reflected this societal shift. The Beatles, a band that began as a direct reflection of mainstream pop, emerged as one of the most influential groups in redefining not only musical boundaries but also social consciousness. Their growth from their image as a lighthearted “boy band” to cultural commentators, mirrored the broader shift of the 1960s counterculture away from conformity and towards experimentation.

The Beatles’ early success was largely attributed to “Beatlemania,” which was rooted in their melodies, coordinated image, and mass appeal, especially to a younger audience. This wave of fan hysteria, especially prominent in the United States following their 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in New York City, represented more than their commercial success. It signaled the start of the youth’s motivations to break free from societal norms and conservatism. While initially dismissed by critics as another pop act, The Beatles quickly evolved, using their growing platform to challenge social norms and political ideologies.

(left) The Beatles’ Abbey Road album cover 1969 via Iain Macmillan (right) and The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, photographer unknown

I visited and photographed the Ed Sullivan Theater, the Imagine Mosaic in Central Park, and the Dakota Building. The Dakota Building apartments are one of New York’s most famous and exclusive residential buildings, and were designated as a New York City landmark in 1969. John Lennon moved into the building in 1973 and lived there with Yoko Ono until 1980, when he was fatally shot while entering the building. The Imagine Mosaic resides across the street in Central Park and is a memorial and gathering place to honor Lennon’s memory and to celebrate the music of The Beatles.

America in the late 1960s was a nation in turmoil and transition. A younger generation was rising up to challenge established power structures, demanding change, freedom, and acceptance. In addition to feeling alienated by the expectations and conservative values of their parents’ generation, many young people embraced the hippie lifestyle not just as a rebellion, but as the foundation for a new worldview that was based on peace, equality, and self-expression. This awakening led many to advocate for real-world change, extending beyond personal liberation.

Hippies of the 1960s, photographers unknown

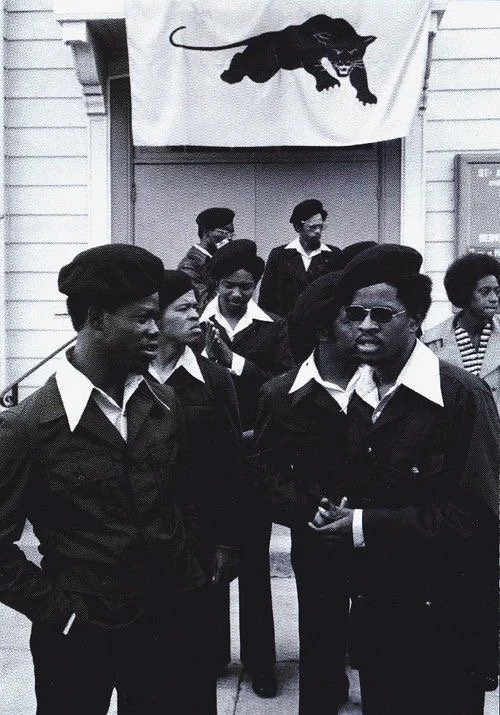

The decade was marked by major political and social movements, most notably the Civil Rights Movement. Groups like the Black Panthers emerged during this time—not only as symbols of Black empowerment, but also as direct responses to racial injustice and police brutality, specifically in places like Oakland, California. While portrayed in the media as aggressive and violent, the Panthers also ran community programs, free breakfast initiatives, and health clinics, employing the vision of social justice.

Black Panthers, photographer unknown

The counterculture itself was multifaceted. It included everything from nonviolent hippies advocating for peace and love to more radical, fighting for systemic change. Student activism was huge, and the movement took on multiple issues, protesting the Vietnam War, fighting for civil rights, women’s liberation, LGBTQ+ rights, environmentalism, and sexual freedom. Massive demonstrations occurred, including a 1969 antiwar protest in Washington, D.C., which had up to 500,000 participants, and the first Earth Day in 1970; a national day of education that signaled the rise of environmental consciousness.

This wave of protest and activism was carried and often led by the music of the time. Artists like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Jefferson Airplane, and The Velvet Underground used their platforms to speak out against injustice, war, and political hypocrisy. Music became both a soundtrack and a motivator for the movement. There was a cyclical relationship: the energy of protest inspired songwriters, whose music helped to incentivize protest, express shared generational frustrations, and strengthen the sense of purpose among the youth.

(left to right) Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, The Velvet Underground, and Jefferson Airplane, photographers unknown

I visited the Stonewall National Monument, which was established in 2016, and features sculptures of couples, one pair standing and the female pair sitting on one of the many benches. On June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village, and one of the few places where LGBTQ+ people, especially those who were gay, transgender, or gender-nonconforming, could gather openly, was raided by police officers who attempted to arrest patrons, the crowd resisted. What began as a routine act of harassment quickly escalated as the bar-goers and other community members pushed back against the police. Although it was not the first instance of LGBTQ+ resistance, the Stonewall uprising marked a turning point. It was a catalyst for the modern gay rights movement in the United States and became a symbol of queer liberation across the world.

The heart of New York’s counterculture was undeniably rooted in Greenwich Village. Over time, the park evolved into a gathering place for a mix of protesters, artists, activists, and musicians, and by 1960, it was overflowing with young, aspiring musicians who played and sang solely for the joy of sharing their music. A cultural revival began to take shape, centered around the park and its surrounding streets. On weekends, folk music was played by amateurs and professionals, the community coming together to appreciate music and spend time together. Musicians mingled with Beat poets, painters, actors, and filmmakers, creating a countercultural space of like-minded creatives. Washington Square became the epicenter of the folk music revival, with more than 20 clubs and coffeehouses, like the Gaslight Café, the Village Gate, Café Wha?, and the Bitter End, all located within a few blocks of each other.

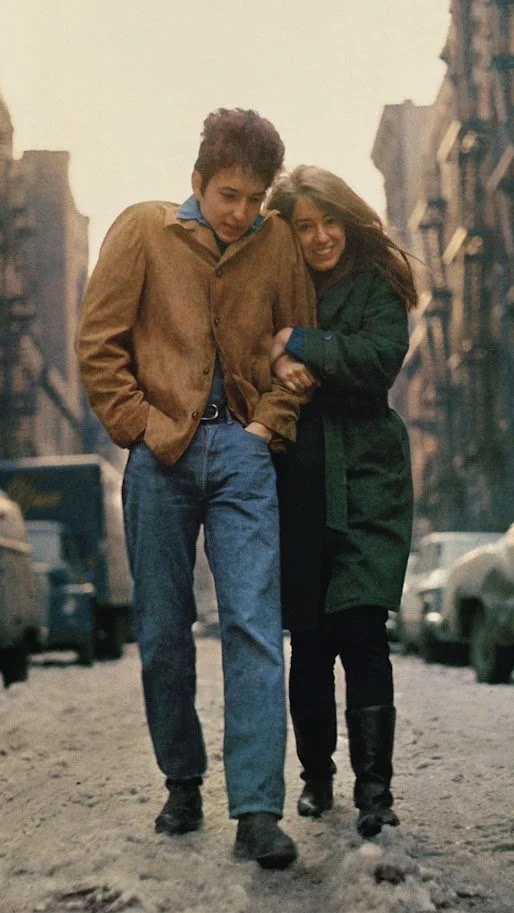

The folk community was bonded by a shared appreciation for traditional pre-war folk music, but it quickly grew into a movement that helped to launch support for the civil rights movement and the growing push for peace. Bob Dylan, a folk rock singer-songwriter and frequent performer at these venues, began his career in the early 1960s with songs that addressed pressing social issues such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. Through his music, Dylan challenged the conservative beliefs of American society, often focusing on individual emotions and personal responsibility rather than broad political ideologies. This made him an influential figure within the counterculture movement of the 1960s, with many young people looking to him for inspiration and guidance on social matters.

Bob Dylan. Left photo photographer unknown, right photo via Don Hunstein

Musical artists like Baez, Dylan, and many others used their work to create dialogue, inspire activism, and reflect the unrest of their generation. Their music was often a response to real-world issues, and much of it carried sharp social and political critique. Within the 1960s folk-rock scene, collaboration was a common practice. Artists regularly covered each other’s songs, appeared on stage together, and supported one another in both artistic and activist efforts. This sense of community didn’t stop within the music industry, but rather extended to the larger countercultural movement and connected to other art forms that were similarly radical.

This interconnected world of folk singers, poets, painters, and revolutionaries helped form a cultural movement rooted in individual expression and community action. Whether it was a protest song sung in Washington Square, a poem that challenged societal norms, or an experimental show or film, every creative effort carried the same sentiments of the movement. Rather than romanticizing the 60s, we should look to it as a lasting source of inspiration. It reminds us that when people unite around shared values, real progress and transformation are possible.

Music in particular proved to be a powerful force: a universal language, a vehicle for protest and poetry, an emotional catalyst, and a foundation for spaces, like festivals and public gatherings, where ideas and movements could grow. Though shaped by the specific cultural and political climate of its era, the counterculture’s legacy continues to show us the power of art and music in shaping people and society.